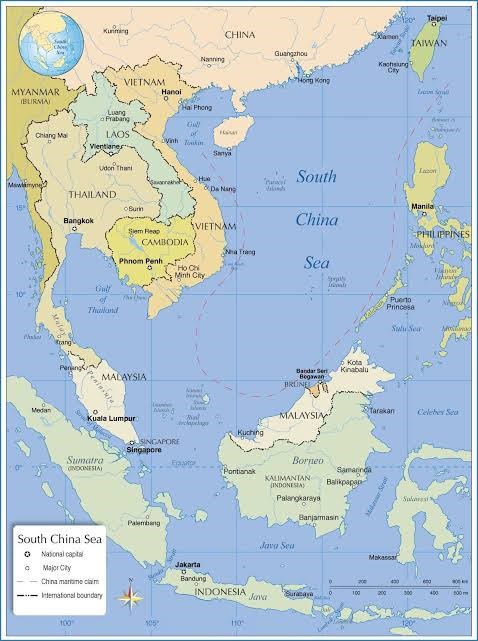

The South China Sea has escalated in significance for both Southeast Asian nations and external powers like the U.S., Japan, Australia, Germany, and France, each increasing their naval presence in these contentious waters. This article argues that instead of unilateral actions, external powers should collaborate more actively with Southeast Asian countries to manage disputes effectively.

The year has seen a pronounced uptick in naval operations; notable incidents include Germany’s warship navigating the Taiwan Strait and France’s aircraft carrier traversing the South China Sea. While the United States has been the most consistent in its “freedom of navigation” operations, nations such as Japan and India are also participating in naval exercises in the area. During the recent Manila Dialogue, European ambassadors emphasized their commitment to regional stability, suggesting an expanded European naval role.

This international presence is largely viewed as a strategy to counter China’s assertiveness in the region. However, Southeast Asian countries exhibit diverse perspectives on this engagement. Some, like the Philippines, welcome Western involvement, particularly from the U.S., while others, including Malaysia and Indonesia, express more caution. China has openly criticized the presence of external powers, arguing that they exacerbate tensions.

The South China Sea’s strategic and economic importance transcends regional borders, prompting a universal interest in maintaining peace. However, it is crucial for external entities to align their actions with the concerns of local nations. Unilateral displays of military presence may escalate tensions rather than foster stability. Instead, more effective engagement could arise from collaboration through military exercises, capacity-building initiatives, and technology transfers that would empower regional coast guards to address issues like maritime cybersecurity.

Three key reasons support this collaborative approach. First, Southeast Asian nations carry historical memories of colonialism and great power competition, breeding skepticism toward extra-regional military presence. Secondly, the desire for ASEAN centrality reflects these nations’ ambition to shape their security landscape, rather than being passive participants amid superpower tensions. They seek a role in determining the nature of external involvement, emphasizing the importance of ASEAN frameworks for cooperation.

Thirdly, unilateral military initiatives carry risks of unintended escalation, as witnessed in past close encounters between U.S. and Chinese forces in the South China Sea. Any confrontation would primarily impact Southeast Asian countries. Australia has demonstrated a constructive model by actively engaging with ASEAN representatives on maritime security concerns and solidifying defense agreements with nations like Indonesia, prioritizing dialogue and capacity development.

Ultimately, the challenge lies not in whether external powers should be present in the South China Sea, but in defining the nature of that presence. The ongoing negotiations on a Code of Conduct between China and ASEAN could play a pivotal role in facilitating external involvement without compromising Southeast Asian nations’ centrality in regional matters. Enhanced collaboration is vital to ensuring that the South China Sea remains a peaceful and lawful maritime environment.