New research shows rising hydrogen emissions since 1990 have indirectly intensified climate change and amplified the impact of methane.

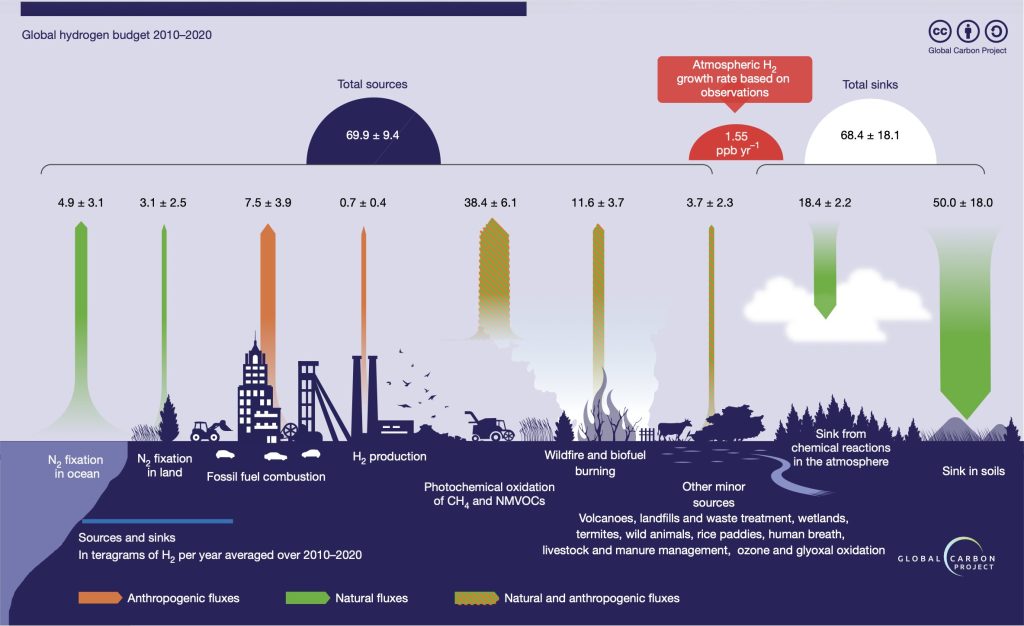

Rising global emissions of hydrogen over the past three decades have added to the planet’s warming temperatures and amplified the impact of methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gases, according to new research published in Nature. Authored by an international consortium of scientists in which IIASA researchers have played an active role for many years, known as the Global Carbon Project, the study provides the first comprehensive accounting of hydrogen sources and sinks.

“Hydrogen is the world’s smallest molecule, and it readily escapes from pipelines, production facilities, and storage sites,” said Stanford University scientist Rob Jackson, senior author of the Nature paper and chair of the consortium. “The best way to reduce warming from hydrogen is to avoid leaks and reduce emissions of methane, which breaks down into hydrogen in the atmosphere.”

Amplifying methane

Unlike greenhouse gases including carbon dioxide and methane, hydrogen itself does not trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere. Through interactions with other gases, however, hydrogen indirectly heats the atmosphere roughly 11 times faster than carbon dioxide during the first 100 years after release, and around 37 times faster during the first 20 years. The main way hydrogen contributes to global warming is by consuming natural detergents in the atmosphere that destroy methane.

“More hydrogen means fewer detergents in the atmosphere, causing methane to persist longer and, therefore, warm the climate longer,” said lead study author Zutao Ouyang, an assistant professor of ecosystem modeling at Auburn University, who began the work as a postdoctoral scholar in Jackson’s lab in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

In addition to extending the heat-trapping life of methane, hydrogen’s reactions with nature’s detergents also produce greenhouse gases such as ozone and stratospheric water vapor, as well as affect cloud formation. The researchers estimate hydrogen concentrations in the atmosphere increased by about 70% from preindustrial times through 2003, then briefly stabilized before picking up again around 2010. Between 1990and 2020, hydrogen emissions increased mostly because of human activities, the authors found.

Vicious cycle

Major sources include the breakdown of chemical compounds including methane, which itself has been

rapidly building up in the atmosphere because of growing emissions from fossil fuels, agriculture, and landfills. It’s a vicious cycle, because methane breaks down into hydrogen in the atmosphere, more methane means more hydrogen. More hydrogen, in turn, means methane emissions stick around longer, doing more damage.

“The biggest driver of hydrogen increase in the atmosphere is the oxidation of increasing atmospheric methane,” said Jackson, the Michelle and Kevin Douglas Provostial Professor at Stanford.

Since 1990, the authors estimate the annual emissions from this source of hydrogen have grown by about 4 million tons, to 27 million tons per year in 2020. Other important hydrogen sources since 1990 include leakage from industrial hydrogen production and the process of nitrogen fixation, which farmers harness to grow legume crops like soybeans. Natural sources of hydrogen, such as wildfires, varied from year to year without a consistent trend across the 1990-2020 period.

Future energy systems

The most detailed data in the study covers the decade ending in 2020, drawing on multiple datasets and models and incorporating emission factors for hydrogen and precursor gases such as methane and other volatile organic compounds. The authors found 70% of all hydrogen emissions were removed during this period by soil, largely through bacteria consuming hydrogen for energy. Overall, the buildup of hydrogen in our atmosphere has contributed a fraction of a degree (0.02°C) to the nearly 1.5°C increase in average global temperatures since the Industrial Revolution.

According to the authors, this temperature increase from rising hydrogen concentrations is comparable to the warming effect of the cumulative emissions from an industrialized nation such as France. Any contribution to warming could diminish the climate benefits of replacing fossil fuels with hydrogen, which has long garnered interest from some politicians, executives, and academics as a clean-burning alternative to oil and gas for heavy industry and transportation.

More than 90% of hydrogen production today is very energy intensive. It’s derived mainly from steam methane reforming or coal gasification, which have large carbon footprints. But because it’s possible in theory to produce hydrogen with renewable energy and close to zero carbon emissions, most scenarios for decarbonizing the world’s energy systems in the coming decades assume low-carbon hydrogen production will increase.

The authors conclude that fully realizing the climate benefits of hydrogen will require a deeper understanding of the global hydrogen cycle and its links to warming, to ensure that a rapidly expanding hydrogen economy remains truly climate-safe and sustainable.

“There is little doubt that cleanly produced hydrogen can play a role in decarbonizing energy systems, but we must better understand its full climate footprint,” notes IIASA researcher and study coauthor Thomas Gasser. “Our findings show that moderate leakage rates and background methane emissions can undermine expected climate benefits. Managing these two factors has to be central to decisions on future hydrogen economy strategies.”

Reference

Ouyang, Z., Jackson, R.B., Saunois, M., Canadell, J.G., Zhao, Y., Morfopoulos, C., Krummel, P.B., Patra, P.K., Peters, G.P., Dennison, F., Gasser, T., et al. (2025). The global hydrogen budget. Nature DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09806-1

About IIASA:

The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) is an international scientific institute that conducts research into the critical issues of global environmental, economic, technological, and social change that we face in the twenty-first century. Our findings provide valuable options to policymakers to shape the future of our changing world. IIASA is independent and funded by prestigious research funding agencies in Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. www.iiasa.ac.at